I now have a grownup professional website. Please redirect your feed readers over there!

October 16, 2015

When history museums interpret stories of colonialism and oppression, words matter. But which words are the right ones? Museums that interpret charged historical stories are often criticized as preachy or politically correct if they use certain words, or cowardly if they avoid them. But words like “colonialism” can also be overdetermined, too filled with ambient cultural meaning for visitors to approach their real significance for people’s lived experiences. Such words can also be too clinical, inadvertently serving to mask experiences and incidents that more specific phrases can reveal.

So how do you choose the right words for exhibit labels that can help visitors engage with histories of oppression? You need to be intentional about some key choices.

Ask for Help

It is logistically and schedule-wise very difficult to run all your labels by your community partner group (you are not planning to develop an exhibit on colonialism by yourself, are you?), but be sure to bring them any particular labels that you have a gut feeling about. Trust your gut and ask for help.

Point of view

First person interpretation is almost always more powerful and emotionally engaging than third. Use labels with bylines and attributions as much as possible as well as quotes from people in the past. People who have lived and are living through colonial violence have a lot to say about their experiences and the experiences of their ancestors. Those voices should be emphasized as much as possible.

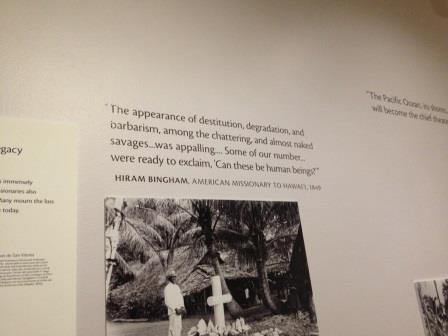

First-person interpretation also works well for people in the past who damn themselves in their own words. Rather than writing a tendentious label saying “Some missionaries did not even think Pacific Islanders were human” I can simply quote Hiram Bingham:

Verb Tense

Many museum labels about indigenous people have historically been written in the “ethnographic present,” a mode that speaks about lifeways as if they are forever unchanging. Labels written in this way suggest that native peoples do not have histories. Ask the people you are making the exhibit with (museums cannot make these shows by themselves) how they would like to talk about their historical situation. It is important for museums to emphasize that indigenous people are still here, and it is important to point out that colonial violence and dispossession still affect people today, but these ideas should also be historicized. Be as specific as possible when you place these stories in time.

Word Choice

There is a lot of blood and pain, lots of ledgers and uniforms and ideas, hiding in the word “colonialism.” Be specific. Talk about specific people losing specific pieces of land, the specific effects of specific diseases on specific communities. Say “blood.” Say “death.” Say “slavery.” Sometimes a simple quote or clearly told story can be more powerful than more academic descriptors in inviting visitors to reflect on stories of colonialism and oppression.

April 1, 2015

There’s been an interesting recent surge of interest in exhibiting religion in museums, particularly history museums. I’m part of an NCPH Working Group this year on Religion, Historic Sites and Museums. The National Museum of American History just had a symposium on religion in early America, with an exhibit on the topic to open in 2017. Colleague Chris Cantwell has been beating the “public history of religion” drum for some time, and there’s a moderately active Religion in Museums blog.

There are some interesting parallel challenges in interpreting the history of religion and my own bailiwick, the history of technology. In fact, I think the technique of “blackboxing” the rightness or wrongness of an idea can be very useful for both fields. A excellent example of this is an exhibit from the 1970s that presented the beliefs and cultural contexts of religious people with great empathy.

I decided to take a look at religion-themed exhibits at my own institution. In 1979, OMCA hosted a exhibition called That Old Time Religion, which evolved out of an art experience Eleanor Dickinson developed at the Corcoran Gallery in 1970. Starting in the late 1960s, Dickinson visited Pentecostal, Holiness, restorationist, and other Spirit-filled churches across Appalachia (and later in California) as an artist-anthropologist. She documented her research through photography, a/v, drawing, (black velvet) painting, and collecting. (Dickinson has an amazing talent for line; she is an artist who can capture faces and emotions vividly in a simple curve.) This documentation became the basis for the Revival! concept, a museum experience that used artifacts and stage setting to invite visitors into a sense of being present at a revival service or tent meeting.

I haven’t found any photographs of the exhibit, but the accompanying book, Revival!, offers a good sense of the gallery experience at the Corcoran.

Eighty-four drawings, many larger than life, lined the walls, but each drawing was titled with the first few lines of a hymn which might be sung at a revival. In the center of the room folding chairs were arranged as if in a revival tent. A Bible rested on a lectern facing the “congregation,” and above it a twelve-foot red-and-white banner proclaimed: LORD SEND A REVIVAL. On the folding chairs were hymnals and paper fans. The hymnals were old, most of them long out of print. It was a warm night–appropriate since most revivals are held in the summer–and many visitors sat and fanned themselves. Some of the fans were old, some new. On one side of each was a religious picture, on the other usually a prayer along with an ad for a funeral parlor in a small southern town.

In an adjoining room were displayed various other artifacts such as posters and flyers announcing revivals, embroidered samplers, bumper stickers, and road signs, all bearing religious messages: PREPARE TO MEET GOD. JESUS IS COMING SOON. From a speaker system the authentic sounds of a revival meeting filled the gallery. The artist had also collected tape recordings of hymn singing, preaching, prayer, testifying, speaking “in other tongues,” and–as is often the case in a revival tent–crying babies, barking dogs, and the sudden thunderstorms common to the Appalachian Mountains.

A previous opening had been held at the Dulin Gallery of Art in Knoxville, Tennessee. There, as in Washington, some came to look at art work and others to worship. Students from the state university called it a trip or a happening. Others wept. Sometimes a visiting preacher delivered a sermon. Later REVIVAL! toured the country, and it was always viewed differently by different groups of people. The artist always insisted on one thing: that is was more than a show of drawings. Perhaps the truth is that by exhibiting the portraits of her people in the setting in which she found them, Eleanor Dickinson had recreated a revival.

Could a show like this tour today? Would it be seen as exoticizing on the one hand or distasteful on the other? Or would visitors today feel the same power the writer in the catalogue found, based on the absolute integrity and sincerity with which Dickinson portrayed her subject-collaborators? A lot has changed in American public cultures of religion since the 1970s, including an increasing ignorance about others’ religions, but interest in the varieties of more extreme religious experiences remains high.

In an interview in Image a few years ago. Dickinson spoke about the value of the emotional experience the show created:

Far from being put off by this unusual use of museum space, the viewing public loved it. “Attendance went way up,” Dickinson remembers. Newsweek reported unusual interest in a “happening” at the museum. Even thirty-five years later, Dickinson takes pride in the show’s authentic recreation of the feeling of the revival. “The janitor at the Dulin Gallery, a preacher himself, told me I’d succeeded in bringing God back into the museum,” she says. She thinks the intensity people felt resided not so much in her drawings as in the “happening.”

At OMCA the show was exhibited in the Hall of California History under the auspices of the History Department, rather than as part of the Art Department’s offerings. What difference did it make for the show to be exhibited as history versus as art? Is religion in the museum more acceptable when presented as art?

Revival!/That Old Time Religion gives us rich material for thinking through the challenges and possibilities of exhibiting religion.

March 14, 2015

Synthetic Thinking Can Be Learned

Posted by Suzanne Fischer under me, public historyLeave a Comment

Or so I attempt to demonstrate in a post up now at History@Work.

February 28, 2015

Here I am complicating the PPIE centennial story in Boom.

August 15, 2014

July 22, 2014

LCM: Does nostalgia play a role in your work?

MD: I try to be historic rather than nostalgic. For me, nostalgia is always tied to the notion of the “Golden Age” of things — this idea that the past was much better. I don’t think that’s true for many things I care about. For women, people of color, gay people, working people, it’s absolutely better now. So I really try to steer clear of golden age thinking and use things to provoke a sense of time and perhaps a sense of loss, but never a sense that somehow our values are worse than the values in the past. I don’t think that’s true. If there’s any reason for optimism, it is that there has slowly been more access to power for more people.

from this Hyperallergic interview

July 21, 2014

July 14, 2014

“the emphatic lives of the long dead”

Posted by Suzanne Fischer under public historyLeave a Comment

But for lovers or friends with no past in common the historic past unrolls like a park, like a ridgy landscape full of buildings and people. To talk of books is, for oppressed shut-in lovers, no way out of themselves; what was written is either dull or too near the heart. But to walk into history is to be free at once, to be at large among people. Art does its work even here in clarifying their faces, but they are dead, immune, their schemes and passions are legacies….Outside, the street, empty, reeled in the midday sun; the glare was reflected in on the gold-and-brown restaurant wall opposite; side by side in the empty restaurant, they surrounded themselves with wars, treaties, persecutions, strategic marriages, campaigns, reforms, successions and violent deaths. History is unpainful, memory does not cloud it; you join the emphatic lives of the long dead. May we give the future something to talk about.

–Elizabeth Bowen, The House in Paris

March 18, 2014

Sustainable Practices for Co-Created Exhibits

Posted by Suzanne Fischer under museums, public history, UncategorizedLeave a Comment

Come to our NCPH session, this Thursday morning at 8:30 as part of the NCPH annual meeting in sunny, convenient Monterey.

How can co-created projects become a sustainable part of our work? This roundtable includes participants who have facilitated recurring co-created exhibits and other projects involving museums, community organizations, students, artists, and other diverse partners. We will discuss the best practices that have emerged from ongoing collaborative projects, followed by a robust discussion with the audience as we collectively outline how we can sustain the co-created projects that keep our institutions responsive, challenging, and vital.

Facilitator: Suzanne Fischer, Oakland Museum of California

Presenters: Lisa Junkin Lopez, Jane Addams Hull-House Museum

Benjamin Cawthra, California State University, Fullerton

Deborah Mack, National Museum of African American History and Culture

Evelyn Orantes, Oakland Museum of California