When history museums interpret stories of colonialism and oppression, words matter. But which words are the right ones? Museums that interpret charged historical stories are often criticized as preachy or politically correct if they use certain words, or cowardly if they avoid them. But words like “colonialism” can also be overdetermined, too filled with ambient cultural meaning for visitors to approach their real significance for people’s lived experiences. Such words can also be too clinical, inadvertently serving to mask experiences and incidents that more specific phrases can reveal.

So how do you choose the right words for exhibit labels that can help visitors engage with histories of oppression? You need to be intentional about some key choices.

Ask for Help

It is logistically and schedule-wise very difficult to run all your labels by your community partner group (you are not planning to develop an exhibit on colonialism by yourself, are you?), but be sure to bring them any particular labels that you have a gut feeling about. Trust your gut and ask for help.

Point of view

First person interpretation is almost always more powerful and emotionally engaging than third. Use labels with bylines and attributions as much as possible as well as quotes from people in the past. People who have lived and are living through colonial violence have a lot to say about their experiences and the experiences of their ancestors. Those voices should be emphasized as much as possible.

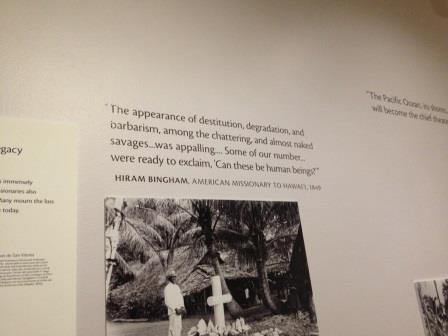

First-person interpretation also works well for people in the past who damn themselves in their own words. Rather than writing a tendentious label saying “Some missionaries did not even think Pacific Islanders were human” I can simply quote Hiram Bingham:

Verb Tense

Many museum labels about indigenous people have historically been written in the “ethnographic present,” a mode that speaks about lifeways as if they are forever unchanging. Labels written in this way suggest that native peoples do not have histories. Ask the people you are making the exhibit with (museums cannot make these shows by themselves) how they would like to talk about their historical situation. It is important for museums to emphasize that indigenous people are still here, and it is important to point out that colonial violence and dispossession still affect people today, but these ideas should also be historicized. Be as specific as possible when you place these stories in time.

Word Choice

There is a lot of blood and pain, lots of ledgers and uniforms and ideas, hiding in the word “colonialism.” Be specific. Talk about specific people losing specific pieces of land, the specific effects of specific diseases on specific communities. Say “blood.” Say “death.” Say “slavery.” Sometimes a simple quote or clearly told story can be more powerful than more academic descriptors in inviting visitors to reflect on stories of colonialism and oppression.

October 17, 2015 at 12:51 pm

Reblogged this on The Museumphiles and commented:

Short but but effective exploration of some challenges face by museums when interpreting colonial histories, with some great suggestions on how to overcome them.

October 22, 2015 at 7:56 am

Good advice! One more suggestion: Active voice. Make it clear that there were colonialists, not just colonialism. People did things. A nice analysis of active and passive voice here, in an article on slavery in textbooks: http://www.nytimes.com/2015/10/22/opinion/how-texas-teaches-history.html